Discovering a New Approach to Gravity

The process by which I came up with a new approach to gravity will be sketched. Due to the constraints of a full time job and family, and being middle aged, I don't have good documentation about what exactly happened when, so this is more impressionistic than something based on careful autobiographical notes.

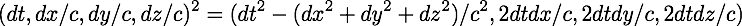

In the Spring ot 2016, I was thinking again about the square of a difference quaternion:

Filed away in my brain was a quote from Abraham Pais' most excellent scientific biography of Albert Einstein, "Subtle is the Lord...", right in the introduction:

Were I asked for a one-sentence biography of Einstein, I would say, 'He was

the freest man I have ever known.' Had I to compose a one-sentence scientific

biography of him, I would write, "Better than anyone before or after him, he knew

how to invent invariance principles and make use of statistical fluctuations.'

Looking at the square of the difference quaternion, the first term is the invariant interval for inertial observers at the cor of special relativity. That term is the reason I purchased quaternions.com in 1997. Oh, and some other stuff. I always wanted the other three terms to have a name. I know I asked on sci.physics.research what the three terms should be called, but that post to the moderated newsgroup was not answered. The Spring of 2016, I came up with a reasonable name of (2 dt dx, 2 dt dy, 2 dt dz) - space-times-time. The name describes exactly what it happens to be.

When two inertial observers agree on the interval between two events, their space-times-time will be different. The precise difference of the space-times-time values can be used to calculate how the two observers are moving relative to each other.

What kind of physics results when two observers find the space-times-time values are invariant, but the intervals are different?

I thought that was a good question.This is what I did in the days after the question was posed...

Nothing.

I have a crazy number of constraints in my life between work, family, diabetes, and this research effort. With so little freedom, I have to make good choices about what questions are good to think about. While walking the dog or shopping for 2% milk for my daughter, I questioned how good was the question itself?

Einstein figured out the physics of special relativity. The physics had logical consequences such as two inertial observers could disagree about events being simultaneous. He was not a math guy. Eventually he was told that the interval was calculated using a metric tensor contracting contravariant 4-vectors. He figured out based on his deep thinking about physics, that such a metric would have to be dynamic in order to explain gravity.

What if instead, Einstein had been told that the math he was doing used the square of a quaternion? That would not change the ability to do any problems in special relativity. I say this based on taking 8.033, Classical and Relativitic Mechanics at MIT in the fall of 1997 and solving every problem set using quaternions (50+ problems in all). I have no doubt that in such an alternative history, in less than two months we would have a simple set of logical questions. Consider two observers looking at a pair of events. They both calculate the difference between the events. They then square this difference. What is the relationship between the two observers in these four cases:

- Both observers agree on the interval and the space-times-time.

- Both observers agree on the interval and disagree on the space-times-time.

- Both observers disagree on the interval and agree on the space-times-time.

- Both observers disagree on the interval and space-times-time.

Case 1 is simple. Nature is consistent. The observers are not moving relative to each other. There is no material difference between the two.

Case 2 is special relativity.

Case 3 requires some thought. Case 2 covers observers traveling at a constant velocity relative to each other, inertial observers, so this must be a different situation, non-inertial observers. How could they agree on their space-times-time? One would have to go up while the other went down.

Imagine two observers. One is lying down on the surface of a planet, the other is up high, carried aloft by some balloons. Balloon girl's heart will be able to beat faster since she is not under as much stress from gravity. Her meter stick will expand too. When she makes a measurement of a pair of events, the time difference will increase due to the faster heart beat while the measured distance will be smaller with a larger meter stick. The lying down man would experience the opposite effects. His heart would beat more slowly while his meter stick got more compressed. That would make the measurements of a time difference larger, but of a distance difference smaller.

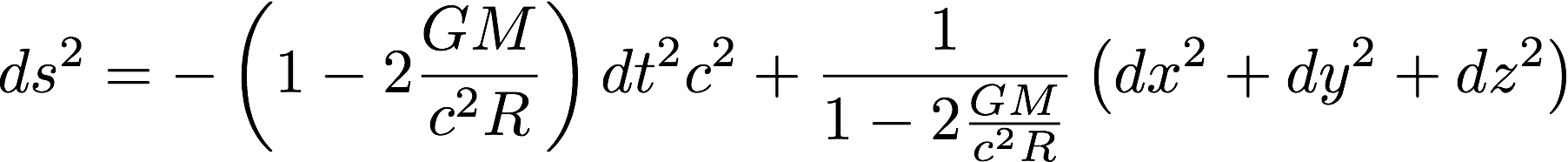

In physics, details matter. While it is the case that going higher in a gravitational field does make the measurements of time increase and space decrease, how do they change exactly? With general relativity, the answer cannot be answered until one has said explicitly what is the choice of coordinates. At some point, I wondered, could there be any overlap between the space-times-time invariance proposal for gravity and standard general relativity? The chapter I studied most closely in Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler was Chapter 40, "Solar-System Experiments". The first unnumbered equation is the Schwarzschild solution in Schwarzschild spherical coordinates. Here is a minor rewrite, the Cartesian form:

It is easy to construct an ad hoc proposal that would be consistent with this result of solving the Einstein field equations and the space-times-time invariance as gravity proposal: